The ear is one of the fascinating organs in the human body. The ears never stop working – even when we are asleep. Our ear contains specialized sense organs that serve two essential functions; they help us hear and maintain balance.

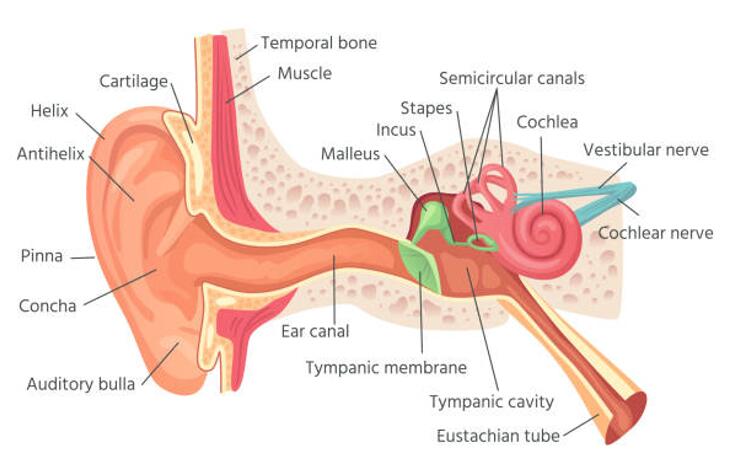

Anatomically, the ear has three parts: The outer, middle, and inner ear. While every part of the ear differs, they work together to detect sounds and facilitate hearing and balance. Although the ear has an unusually complex anatomy, it is easy to understand. In this article, we describe the ear’s anatomy in simple terms.

Parts of the Ear: Anatomy and Physiology of the Ear

1. The Outer ear (Auricle or Pinna)

Our outer ear, made of cartilage and skin, comes in different shapes and sizes. The varying structure is what gives each of us our distinctive appearance. Although our outer ear plays a minor role in our ear’s hearing function, it provides essential protection and structure.

The external parts of your heating system, often referred to as the outer ear, are made up of the pinna (your ear flap), the visible part of the ear seen on the side of the head. The pinna’s job is to collect and focus sound waves toward your ear canal.

The outer ear has a dish-like shape which helps to collect sound waves. This sound collection is the primary purpose of all external ear auricle anatomy.

The external ear can be divided structurally and functionally into the auricle (or pinna) and the external auditory canal, which ends at the tympanic membrane (eardrum).

The Auricle

The auricle (or pinna) is a paired structure on both sides that collects and focuses sound waves into the external auditory canal. The external auditory canal is a short tube that runs from the auricle to the tympanic membrane (eardrum).

The eardrum separates the outer ear from the middle ear, containing three tiny bones: the malleus, incus, and stapes. The eardrum vibrates in response to sound waves traveling down this canal. These vibrations are passed on through the middle ear bones to the cochlea in the inner ear.

The auricle is divided into three parts; the tragus, helix, and lobule. The auricle is mostly a cartilaginous structure, except for the lobule, which is the only part not made of cartilage.

Helix

The helix is the outermost curvature of the ear that starts where the ear joins the head at the top and ends where your head meets your lobule. The helix helps to channel sound waves into the ear.

Fossa, superior crus, inferior crus, and antihelix: These outer ear sections form the middle ridges and depressions of the outer ear.

The superior crus is the first ridge that appears to be moving from the helix. The inferior crus is the continuation of the superior crus, separating off toward the head. The antihelix is the lowest extension in this section, while the fossas are the depressions between the ridges. These sections direct sound waves collected at the helix toward the middle ear.

Concha: The concha is the depression at the outer ear leading to the opening of the middle ear or the external acoustic meatus. The concha is the final point of the external ear that directs sound into the middle ear.

Tragus and antitragus: These two arch-shaped cartilage structure encloses the concha on both sides.

The lobule is the bottom-most part of the ear, also called the earlobe. The ear lobe is the only part of the outer ear that is not supported by cartilage. The lobule is soft and contains a larger blood supply than the rest of the ear, which may help keep the rest warm.

External acoustic meatus: The external acoustic meatus, also known as the ear canal, is an inch-long passageway connecting the outer and middle ear.

The external acoustic meatus does not have a straight path and instead travels in an S-shaped hollow tube that curves slightly downward as it moves into the ear toward the tympanic membrane or eardrum.

Tympanic membrane

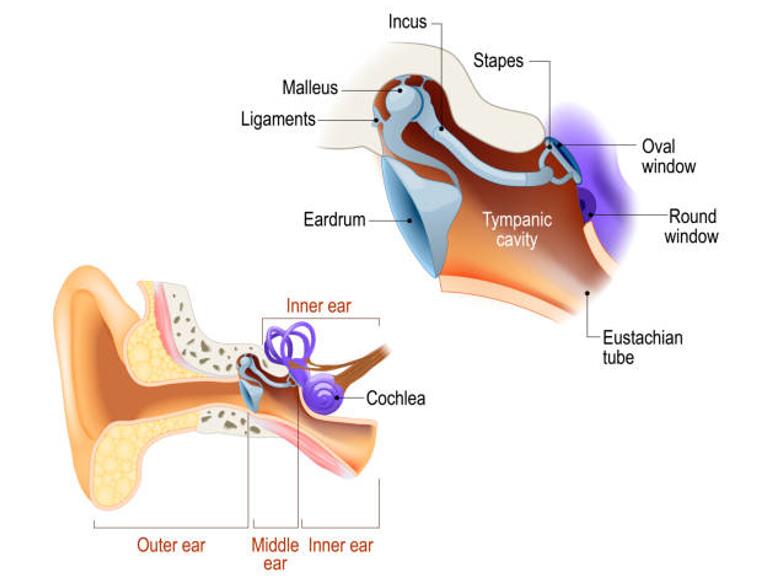

The eardrum, or the tympanic membrane, is the final point in the external ear and the beginning of the middle ear.

The tympanic membrane comprises a thin connective tissue membrane covered by a layer of skin on its lateral surface (facing the external acoustic meatus) and a mucous membrane on its internal surface (facing the middle ear).

The tympanic membrane helps to transfer vibrating signals to the middle ear. The external surface of the tympanic membrane is concave, and the internal surface is convex.

The annulus is a fibrocartilaginous ring that attaches to the temporal bone and surrounds the tympanic membrane.

The umbo is a concave depression that sits at the center of the tympanic membrane and attaches to the handle of the malleus, one of the auditory ossicles in the middle ear.

The tympanic membrane can be further subdivided into two regions:

The pars flaccida: where the membrane is thin and slack (small upper portion)

The pars tensa: where the membrane is thick and taut.

2. Anatomy of The Middle Ear

The middle ear or middle ear cavity is an air-filled chamber that lies in the petrous part of the temporal bone. The primary function of the middle ear is to funnel sound waves from the outer ear to the inner ear.

The middle ear is also called the tympanic cavity or tympanum. The tympanic membrane separates the external and middle ear, and the tympanic cavity separates the middle and inner ear.

The Tympanic Cavity

Medial to the tympanic membrane is the tympanic cavity, which essentially makes up the middle ear. The tympanic cavity or middle ear is an air-filled, membrane-lined space between the ear canal and the cochlea, auditory nerve, and the Eustachian tube. The eardrum separates this space from the ear canal.

The lateral wall is made up of the tympanic membrane. The roof separates the middle ear from the middle cranial fossa. The floor divides the middle ear from the jugular vein.

The medial wall separates the middle ear from the inner ear and is characterized by an evident projection created by the facial nerve. The anterior wall separates the middle ear from the internal carotid artery and has two holes for the tensor tympani muscle and one for the auditory tube.

The posterior wall is a bony partition that separates the middle ear and the mastoid air cells. A superior hole in the rear wall (called aditus to the mastoid antrum) allows communication between the middle ear and the mastoid air cells.

The Ossicles

The middle ear has three tiny bones called ossicles that help conduct sound. They are called the malleus (the hammer), incus (the anvil), and stapes (the stirrup).

Ligaments and synovial joints connect the ossicles. Sometimes the three bones are referred to as the ossicular chain. The chain carries sound vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the oval window.

Fun fact: The stapes are the smallest bone in the human body.

The Auditory (Eustachian) Tube

The auditory tube links the middle ear to the nasopharynx (back of the throat).

The auditory tube helps to aerate the middle ear and removes mucus and unwanted debris, thus preventing infection from ascending to the middle ear.

The inside of the tube is lined with cilia, tiny hairs that sweep mucus out of the tube where it drains into the back of the throat. The auditory tube of an adult auditory tube is approximately 31 mm to 38 mm in length, while it is much smaller in a child.

The normal opening of the auditory tube equalizes atmospheric pressure in the middle ear; closing the eustachian tube protects the middle ear from unwanted pressure fluctuations and loud sounds.

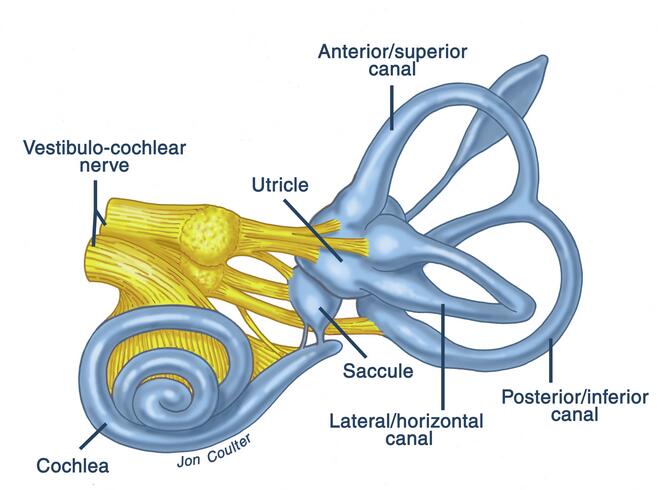

3. Anatomy of the Inner Ear

The inner ear, also known as the ear’s labyrinth, is part of the ear that is responsible for hearing and postural balance. The inner ear’s anatomy is designed to transfer the mechanical energy transmitted in sound waves generated by surrounding objects into neuronal impulses (transduction) that can be interpreted as sound.

The bony labyrinth, a cavity in the temporal bone, comprises a membranous labyrinth divided into the vestibule, semicircular canals, and cochlea.

The vestibule

The vestibule of the ear is a bony cavity within the temporal bone that contains otolith organs and nerves related to the vestibular system. It lies in the inner ear between the tympanic cavity behind the cochlea, lateral to the oval window, and anterior to the semicircular canals.

The vestibule contains the otolith organs, called the utricle and saccule, which are essential for controlling our equilibrium and balance.

The semicircular canals

Your semicircular canals are three small, interconnected fluid-filled tubes in your inner ear whose principal role is keeping your balance and head position. When you move your head around, the liquid inside the semicircular canals splashes around and moves the tiny hairs that line each canal.

The movement of the hairs sends a message to your brain that your head is spinning. When that happens, your brain tells your body how to stay balanced.

The cochlea

The cochlea is one of two main structures that make up the inner ear. It is a snail-shaped organ that contains the sensory organ of hearing (Corti).

The cochlea is a hollow, spiral-shaped bone found in the inner ear that plays a significant role in the sense of hearing. It can transduce the sound waves into electrical impulses the brain can interpret as individual sound frequencies.

The cochlea is divided into three parts: The scala vestibule, vestibular duct, The scala tympani (tympanic chamber), The scala media, or the cochlear duct.

Wrap Up

Although the ear is small, it is essential for hearing and balance. The ear’s anatomy is complex, but understanding it allows you to know how the ear works.