White blood cells (WBCs), also known as leukocytes, are the soldiers of the body’s immune system. They circulate in the blood, constantly looking for invaders like bacteria, viruses, and parasites. When they detect a threat, they launch a coordinated attack to neutralize the enemy and protect the body from harm. A white blood cell count is a key measure of immune system function. It tallies the number of WBCs in a sample of blood. The count can reveal if the immune system is fighting an infection. This article will discuss what a normal WBC count looks like, and what it means when counts are too high or too low.

What is a Normal White Blood Cell Count?

In a healthy adult, the white blood cell count usually falls in the range of 4,000 to 11,000 cells per microliter (μL) of blood. This can also be expressed as 4.0 to 11.0 x 10^9/L. However, there are some nuances to this “normal” range:

- Age: Babies and children tend to have higher WBC counts than adults. Newborns can have up to 30,000 WBCs per microliter, while infants and toddlers often have counts in the range of 6,000 to 17,000.

- Sex: Women typically have slightly lower WBC counts than men. For adult women, 4,500 to 11,000 WBCs per microliter is considered normal, while for men, it’s 5,000 to 10,000.

- Pregnancy: WBC counts often rise during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester. Counts up to 15,000 per microliter can be normal in healthy pregnant women.

- Racial and ethnic differences: Some studies suggest that people of African descent may have lower baseline WBC counts than those of European descent. However, these differences are relatively small.

It’s important to remember that a “normal” WBC count is a range, not a single number. Counts can vary from person to person and can fluctuate in the same person from day to day or even hour to hour. Factors like stress, exercise, and smoking can cause WBC counts to spike temporarily.

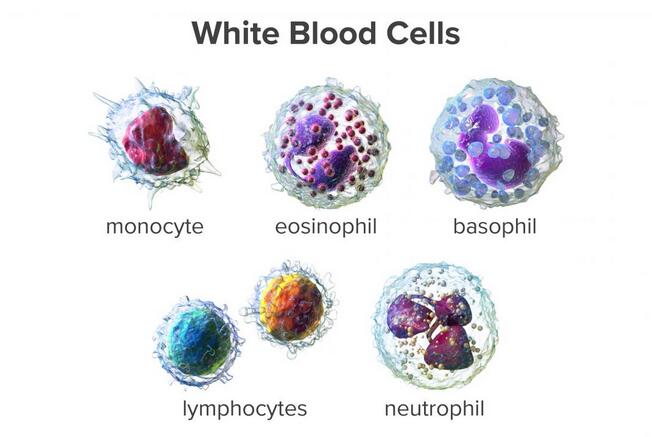

Types of White Blood Cells

White blood cells are not a homogeneous army. There are five main types of WBCs, each with specialized functions and unique abilities. A WBC differential test provides a breakdown of the percentages of each type. Here’s a closer look at these cellular soldiers:

1. Neutrophils

These are the most abundant WBCs, usually making up 55-70% of the total count. They’re the immune system’s first responders, quickly migrating from the bloodstream into infected or inflamed tissues.

Neutrophils are phagocytes, meaning they engulf and digest bacteria and other microbes. They also release chemicals that kill microbes and signal other immune cells to join the fight.

2. Lymphocytes

The second most common type of WBC (20-40%), lymphocytes are the special forces of the immune system. There are two main types: B cells and T cells. B cells produce antibodies, Y-shaped proteins that latch onto specific invaders and mark them for destruction.

T cells directly attack infected, cancerous, or otherwise abnormal cells. Some T cells also help coordinate the immune response by secreting chemical messengers.

3. Monocytes

These are the largest WBCs, making up 2-8% of the total. Monocytes patrol the bloodstream and tissues, engulfing bacteria, dead cells, and other debris. When they take up residence in tissues, they mature into macrophages and dendritic cells. These cells not only devour microbes but also help activate T cells and B cells.

4. Eosinophils

Normally making up just 1-4% of WBCs, eosinophils are specialists in combating parasites and modulating allergic responses. They contain granules filled with enzymes that are toxic to parasites and that also help regulate inflammation. The number of eosinophils can spike during allergic reactions and parasitic infections.

5. Basophils

The rarest of the WBCs (<1%), basophils are also involved in allergic responses. When activated, they release histamine, a chemical that causes blood vessels to dilate and become leaky. This leads to the typical symptoms of an allergic reaction like a runny nose, itchy eyes, and hives. Basophils also release chemicals that attract other WBCs to sites of inflammation.

High White Blood Cell Count (Leukocytosis)

A high WBC count, also known as leukocytosis, is usually a sign that the body is dealing with an infection, inflammation, or stress. The threshold for leukocytosis varies slightly by lab but is generally considered to be a count greater than 11,000 cells/μL in adults. Some common causes of an elevated WBC count include:

- Bacterial infections: When bacteria invade the body, neutrophils rush to the scene to engulf and destroy them. The bone marrow also ramps up the production of new neutrophils, leading to an increase in the total WBC count. The degree of leukocytosis often correlates with the severity of the infection.

- Inflammation: Conditions that cause chronic inflammation, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and vasculitis, can drive up WBC counts. The inflammatory chemicals released by damaged tissues attract WBCs, particularly neutrophils and monocytes.

- Stress: Both physical and emotional stress triggers the release of hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, which can boost WBC counts. Even the stress of strenuous exercise can cause a temporary spike in WBCs.

- Medication: Certain drugs, including corticosteroids, lithium, and beta-agonists (used to treat asthma and COPD), can increase WBC production or mobilize WBCs from the bone marrow into the bloodstream.

- Smoking: Cigarette smoking causes chronic inflammation in the lungs, which leads to persistently elevated WBC counts. This effect can last for years after quitting.

- Cancer: Blood cell cancers like leukemia and lymphoma are characterized by the uncontrolled growth of abnormal WBCs. Solid tumors that have spread to the bone marrow can also disrupt normal WBC production and lead to leukocytosis.

In some severe infections, the WBC count can skyrocket to over 30,000 cells/μL. This extreme elevation is called a leukemoid reaction and can initially be confused with leukemia. However, the WBC count quickly returns to normal once the infection is treated, which helps distinguish it from cancer.

Low White Blood Cell Count (Leukopenia)

On the other end of the spectrum, a low WBC count, or leukopenia, means the body’s defenses are down. This leaves a person more vulnerable to infections, even from microbes that normally don’t cause serious illness. Leukopenia is generally defined as a WBC count below 4,000 cells/μL in adults. Some conditions and factors that can lead to a low WBC count include:

- Viral infections: While bacterial infections typically increase WBC counts, some viral infections like influenza and COVID-19 can temporarily suppress WBC production in the bone marrow, leading to leukopenia.

- Autoimmune disorders: In autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, the immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys its cells, including WBCs. Some autoimmune conditions can also damage the bone marrow, impacting its ability to produce new blood cells.

- Bone marrow disorders: Conditions that damage the bone marrow or replace normal marrow with abnormal cells can impair WBC production. These include blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma, as well as some non-cancerous conditions like aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndromes.

- Nutrient deficiencies: A lack of certain nutrients that are essential for WBC production, such as vitamin B12, folate, and copper, can lead to leukopenia. These deficiencies can be due to inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption disorders, or other underlying health conditions.

- Chemotherapy: Cancer-fighting drugs often indiscriminately destroy fast-growing cells, including WBCs and other blood cells. Chemotherapy-induced leukopenia is a common side effect that increases the risk of serious infections, often requiring adjustments to the treatment regimen.

- Radiation exposure: High doses of radiation, such as from radiation therapy for cancer, can damage the bone marrow and cause leukopenia. The severity and duration of the leukopenia depend on the dose and duration of the radiation exposure.

- Certain medications: Some drugs can cause leukopenia as a side effect by suppressing WBC production or destroying circulating WBCs. These include certain antibiotics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and medications for an overactive thyroid.

A particularly low level of neutrophils, the most abundant type of WBC, is called neutropenia. This is often defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) below 1500 cells/μL. Severe neutropenia (ANC <500 cells/μL) leaves people highly vulnerable to bacterial and fungal infections that can quickly become life-threatening.

Diagnosis of Abnormal WBC Counts

WBC counts are routinely checked as part of complete blood count (CBC) tests, often done during regular check-ups or when a doctor suspects an infection or other medical problem. If the WBC count is found to be abnormal, the doctor will consider this result in the context of the person’s symptoms, physical exam findings, and other test results.

Additional tests may be ordered to help determine the underlying cause of the abnormal WBC count. These may include:

- Blood cultures to check for bacteria in the bloodstream

- Imaging tests like X-rays or CT scans to look for signs of infection or inflammation

- Bone marrow biopsy to examine WBC production and rule out blood cancers

- Tests for inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Specific tests for autoimmune diseases, vitamin deficiencies, or genetic disorders that can affect WBC counts

Treatment for abnormal WBC counts

Based on the information provided in the search results, here are the key points about treatment for abnormal white blood cell (WBC) counts:

Treatment for High WBC Count (Leukocytosis):

- Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause of the elevated WBC count.

- For bacterial infections, antibiotics may be prescribed to treat the infection and lower the WBC count.

- For inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, medications to reduce inflammation such as corticosteroids may be used.

- Certain medications that can increase WBC counts, like steroids, may need to be adjusted or stopped.

- In cases of extreme leukocytosis, such as leukemoid reactions or leukemia, treatments like chemotherapy, radiation, or stem cell transplants may be required to lower the WBC count.

- If the high WBC count leads to blood thickening (hyperviscosity syndrome), emergency treatments like leukapheresis (removing WBCs from the blood) may be needed.

Treatment for Low WBC Count (Leukopenia):

- Treatment aims to address the underlying condition causing the low WBC count.

- Medications that can suppress WBC production, like chemotherapy drugs, may need to be stopped or adjusted.

- For nutrient deficiencies contributing to leukopenia, supplements like vitamin B12 or folate may be given.

- Drugs that stimulate WBC production, like granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), may be used after chemotherapy to boost low counts.

- In cases of severe leukopenia, a referral to a hematologist (blood specialist) may be recommended.

- Preventive measures like a low-bacterial diet and avoiding infection exposure may be advised for very low WBC counts.

FAQs

Here are some common questions and answers about white blood cell counts:

1. What does it mean if my white blood cell count is high?

A high white blood cell count (leukocytosis) is often a sign that your body is fighting an infection, dealing with inflammation, or under significant stress.

Some common causes of a high WBC count include bacterial infections, inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, physical or emotional stress, certain medications, and blood cancers like leukemia.

2. What does it mean if my white blood cell count is low?

A low white blood cell count (leukopenia) means that your body’s defenses against infections are weakened. This can make you more susceptible to serious infections.

Some common causes of a low WBC count include viral infections, autoimmune disorders, bone marrow disorders, nutrient deficiencies, chemotherapy, radiation exposure, and certain medications.

3. How often should I get my white blood cell count checked?

For most people, white blood cell counts are checked as part of a routine complete blood count (CBC) during annual check-ups. However, if you have a condition that affects your white blood cell count.

Or if you are undergoing treatment that can impact your counts (like chemotherapy), you may need more frequent tests. Your doctor will determine the appropriate testing frequency based on your health situation.

4. What should I do if my white blood cell count is abnormal?

If your white blood cell count is found to be abnormally high or low, your doctor will likely recommend additional tests to determine the underlying cause. This may include blood tests, imaging scans, or a bone marrow biopsy.

Treatment will depend on the specific cause identified. In some cases, like a mild viral infection, no treatment may be necessary and the count will return to normal on its own. In other cases, like a serious bacterial infection or blood cancer, prompt treatment will be essential.